Defending Britain’s Future: How Engineers Are Reinventing Flood Resilience

Britain’s flood risk is rising as heavier rainfall meets ageing infrastructure and slowly rising seas. Policy is shifting, budgets are growing, and engineering practice is moving from reactive works to adaptive systems. The central truth holds: resilience isn’t just concrete, it’s foresight, data, and long-term discipline.

The Scale of Risk and the Direction of Travel

England’s six-year investment plan allocates £5.2 billion (2021–2027) to flood and coastal erosion risk management, targeting around 336,000 additional properties protected. This marks a step change over the previous programme and anchors hundreds of schemes now in delivery.

Risk exposure remains large. The Environment Agency’s latest national assessment indicates about 6.3 million properties in England are at some level of flood risk, a figure projected to rise by mid-century.

Economic impacts are significant: government and parliamentary sources estimate annual flood damages in the range of £1.3–£2.4 billion, depending on the scale of events and methodology used.

From Static Defences to Adaptive Systems

The Thames Estuary 2100 (TE2100) programme is the UK’s flagship for adaptive pathways — monitor change, set trigger points, and upgrade on evidence rather than on fixed dates. Reviews every five years and plan updates every decade embed this discipline into delivery.

This adaptive logic is spreading. Programmes now combine hard assets, operational rules, nature-based measures and data-led maintenance to manage performance over decades, not merely survive the next storm. Benefit–cost studies consistently show strong returns: typically £5–£8 of avoided damage for every £1 invested over an asset’s life cycle.

Engineering With Nature and Managing Surface Water

Nature-based measures and sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) have become mainstream complements to walls, gates and pumps. Major urban developments — for example in Greater Manchester — are designed with permeable surfaces, attenuation features, blue-green corridors and planned exceedance routes to ease pressure on combined systems.

The Somerset Levels floods of 2013/14 remain a case study for catchment-scale management and the economics of prevention, with total impacts assessed above £100 million. They demonstrated that joined-up management is cheaper than emergency response.

Data-Led Operations and Predictive Maintenance

The frontier now is data. Across flood assets managed by the Environment Agency and local authorities, telemetry and condition records are being integrated to support predictive maintenance and proactive interventions — the operating logic behind TE2100 and the national FCERM strategy.

During Storm Babet (October 2023), the Environment Agency reported that around 100,000 properties were protected by existing defences, even as several regions still experienced flooding. The lesson is clear: asset data and coordinated management are now as vital as concrete and steel.

Case Notes: Hull, the Estuary and Catchments

Hull & the Humber frontage: the £42 million Humber: Hull Frontages tidal scheme, completed in 2021, forms part of a wider regional programme providing better protection to around 113,000 homes. Since 2015, over £260 million has been invested in the city’s flood infrastructure.

Thames Estuary: TE2100 manages roughly 330 kilometres of tidal defences and over 4,000 individual assets — barriers, outfalls, gates and pumping stations — within a single adaptive framework designed to evolve with sea-level projections.

National perspective: the 2015–16 winter floods caused an estimated £1.6 billion in damages across England. Earlier events, notably 2007, revealed how rapidly costs escalate when fluvial, tidal and surface-water systems interact without coordination.

System Constraints to Solve

Flood management in England is split across multiple risk management authorities — the Environment Agency (main rivers and coast), lead local flood authorities (surface water), water companies (sewers) and internal drainage boards (lowland drainage). Coordination and data interoperability remain persistent challenges identified by professional bodies and parliamentary committees.

Funding also needs long-term consistency. Expert analysis suggests around £1.5 billion per year would be required to maintain standards as climate pressures rise — roughly matching the scale of the challenge but above current allocations.

International Lens: What the Netherlands Gets Right

The Netherlands manages flood risk through Rijkswaterstaat and regional water boards under the Delta Programme, formalised by the Delta Act (2012). Dutch policy has shifted to risk-based standards, targeting by 2050 a base protection level of 1-in-100,000 annual fatality risk for those living behind the primary dike system.

Roughly 26% of Dutch land lies below sea level, and nearly half would be flood-prone without defences — a national reality that drives coherent governance and funding. The country’s success lies not only in engineering but in its institutional foresight: statutory programmes, clear accountability, and infrastructure designed for continuous upgrading.

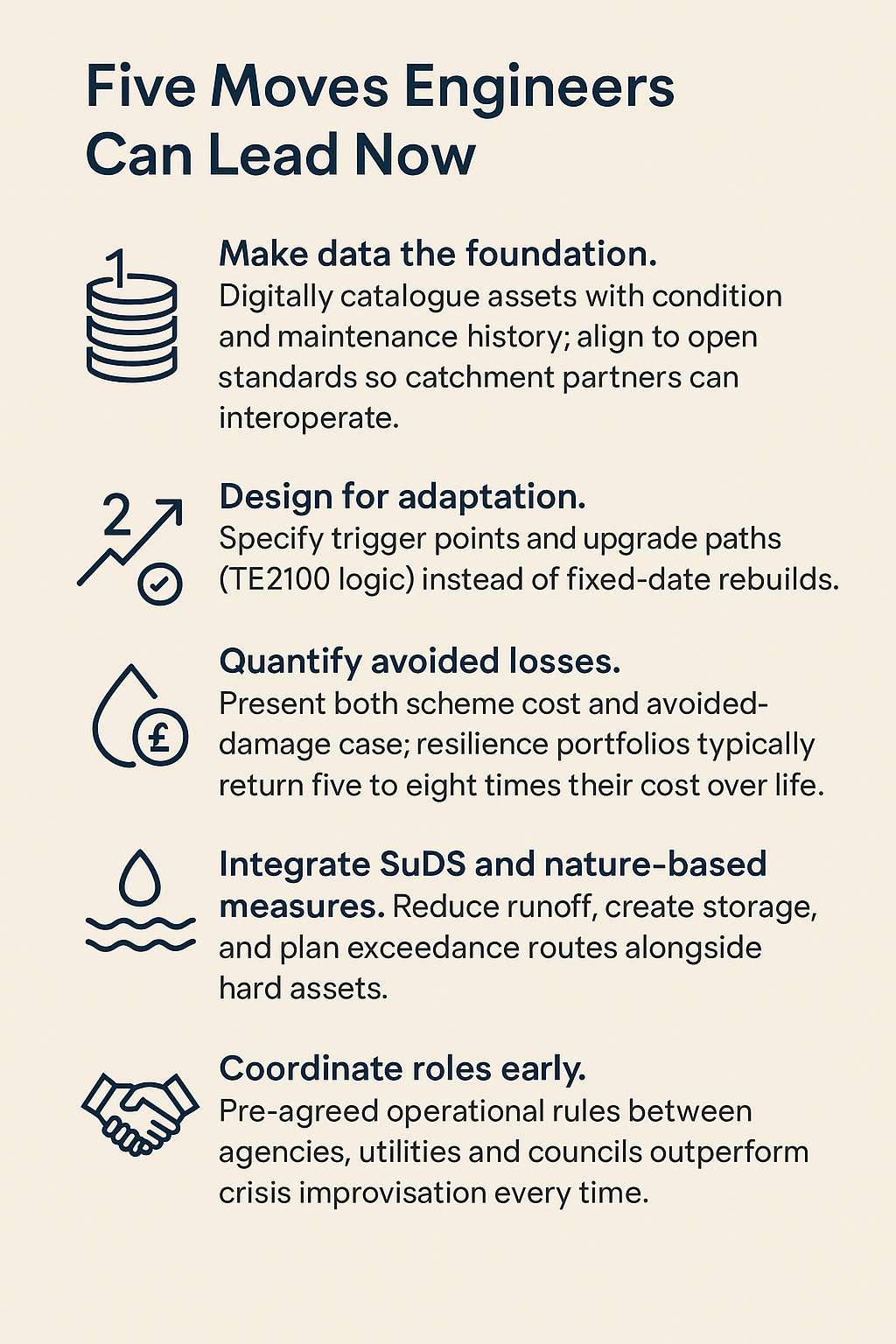

Five Moves Engineers Can Lead Now

1. Make data the foundation. Digitally catalogue assets with condition and maintenance history; align to open standards so catchment partners can interoperate.

2. Design for adaptation. Specify trigger points and upgrade paths (TE2100 logic) instead of fixed-date rebuilds.

3. Quantify avoided losses. Present both scheme cost and avoided-damage case; resilience portfolios typically return five to eight times their cost over life.

4. Integrate SuDS and nature-based measures. Reduce runoff, create storage, and plan exceedance routes alongside hard assets.

5. Coordinate roles early. Pre-agreed operational rules between agencies, utilities and councils outperform crisis improvisation every time.

EnginEdge Perspective

The UK now has the policy scaffolding (FCERM investment plan, TE2100), the technical capability, and strong economic evidence for resilience. What’s missing is simple but decisive: clear governance, interoperable data, and stable long-term funding that matches climate risk.

Get those right, and the most successful projects will be the ones the public never hears about — because the flood never arrives.